Transforming Clinical Trials: Adaptive Approaches for Better Patient Outcomes

1. Introduction

Clinical trials have revolutionized healthcare, transforming human lives by enabling the development of new and effective treatments. These trials are the cornerstone of medical advancements, ensuring that new therapies are safe and effective before reaching the public. However, traditional clinical trials, characterized by fixed sample sizes, allocation, and entry criteria, often involve lengthy processes where data analysis occurs only after the trial’s completion. This rigid approach, rooted in a 75-year-old design methodology, can lead to inefficiencies and ethical concerns, as it necessitates guessing at crucial parameters such as doses, patient populations, and treatment durations. Also a common “Theraputic misconception” exists among patients who are thinking about taking part in clinical trials. Trial participants and family members sometimes think that the purpose of a clinical trial is to improve their own outcomes. This misconception is frequently exacerbated by media advertisements for clinical research. Clinical trials primarily aim to evaluate the effect of a treatment on disease outcomes. Comparisons are typically made with standard of care for conditions that have effective treatments and with placebo for conditions that do not yet have an established treatment. Any advantage received by a single trial participant is the result of randomization’s chance effect combined with the actual, but unidentified, relative effects of the treatments.

There is conflicting evidence currently available regarding the potential benefits that patients derive from merely taking part in clinical trials. Therefore, despite the fact that taking part in research is fundamentally an altruistic endeavor, many volunteers for clinical trials do not do so out of altruism. It is possible to raise the possibility that study participants will gain something from participating in a clinical trial by using an adaptive clinical trial design, which is topic of discussion of today’s post. Obviously you don’t want to end up like Mr. Hiram here!

2. But what are adaptive clinical trials

Imagine you’re playing a game where you have to guess how much candy is in a jar. In a traditional way, you’d guess once and wait until the end to see if you’re right. But what if, during the game, you could get hints to adjust your guess as you go along? That’s kind of like how adaptive clinical trials work!

In regular clinical trials, scientists decide everything at the start and can’t change anything until the end, which can take years. It’s like making one big guess and sticking with it. But with adaptive clinical trials, scientists can make changes as they see how things are going. If they notice something isn’t working well, they can try a different approach right away.

This way, they can find the best and safest treatments for patients faster. So, adaptive clinical trials are like getting helpful hints during the game, making it easier to win and making sure everyone has a better chance of getting the right amount of candy!

To further understand adaptive designs, it may be helpful to first consider a traditional fixed trial design. In a fixed design, the sample size, allocation, and entry criteria are predetermined and unchanging. The data is not analyzed until the trial is completed, often years after it started. This 75-year-old approach imposes strict constraints, forcing the design team to make early guesses about doses, range, patient population, treatment duration and frequency, and other factors. A fixed design necessitates a linear effort for each treatment arm.

An adaptive design, on the other hand, is like driving with your eyes open. It allows for pre-specified flexibility in key trial aspects such as treatment arms (dose, frequency, duration, combinations), allocation to treatment arms, patient population, and sample size. Adaptive designs learn from accumulating data to identify the most effective doses or treatment arms, refining the trial as it progresses. This flexibility enables starting with a broader range of doses—perhaps 8 instead of 3—while using fewer patients overall. The result is a smarter design that uses resources (including time) more efficiently and enhances scientific precision. Well-constructed adaptive designs benefit everyone involved: they provide better learning, are more efficient, offer improved treatment for trial subjects, and deliver better information for regulators and the medical community.

The main drawback of adaptive designs is that they are more complex to develop. They require clinical trial simulations to ensure the design functions well, meets regulatory standards, and is efficient. Creating an adaptive design involves collaboration among statisticians, clinicians, marketing teams, regulatory experts, execution teams, and drug supply managers to construct a highly efficient trial.

3. Dynamic Treatment Allocation

Randomization is crucial in clinical trials to provide an unbiased comparison between new and standard therapies by balancing both measured and unmeasured covariates. Most trials use a 1:1 randomization scheme, which is suitable given the initial state of clinical equipoise. However, many participants are uncomfortable with random treatment assignment and would prefer a new treatment or an expert’s decision.

As the trial progresses, knowledge about the treatments’ effectiveness accumulates, but fixed assignment ignores this information, potentially leading to some patients receiving inferior therapy. While the primary goal of the trial should not be compromised, using interim data could improve outcomes for participants, especially those enrolling later, by increasing the likelihood of receiving the better treatment.

Adaptive clinical trials address this issue by allowing adjustments to key characteristics—such as randomization ratio and interim analysis frequency—based on accumulating data and pre-defined decision rules. This approach requires extensive numerical simulation to maintain statistical validity and control the false-positive rate.

4. An adaptive randomisation trial

Giles et al. conducted a randomized trial comparing three induction therapies for elderly patients with previously untreated, adverse karyotype acute myeloid leukemia. The standard regimen of idarubicin and ara-C (IA) was compared against two experimental regimens involving troxacitabine with either idarubicin (TI) or ara-C (TA). The primary endpoint was achieving complete remission (CR) without non-hematological grade 4 toxicities within 50 days; In other words, patients shpuld get better. If this is overwhelming, just remember that there were three treatments arms IA (Standard of Care), TI & TA (which were compared with Standard of Care)

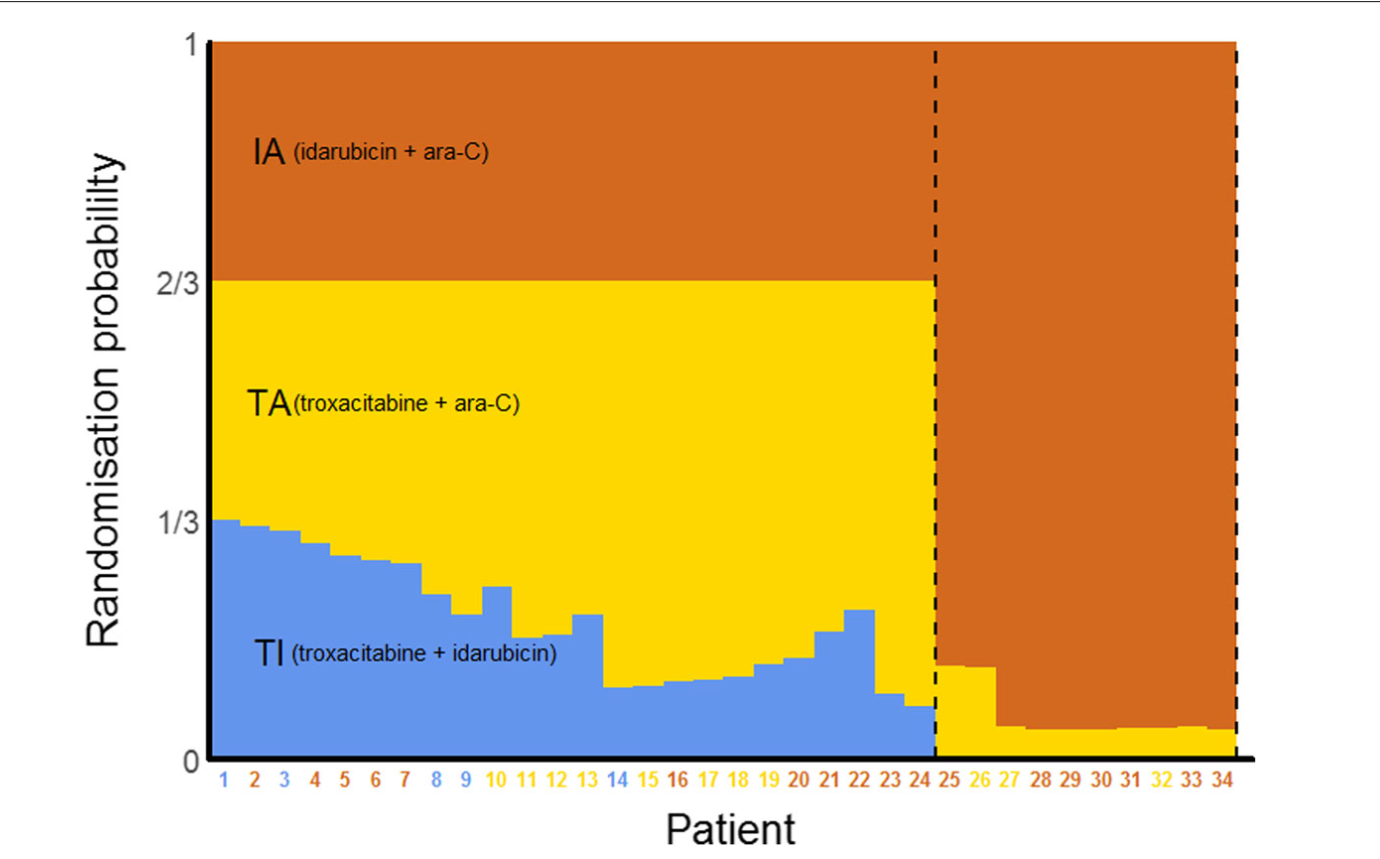

Initially, patients were equally randomized to the three arms, but the trial used a response-adaptive randomization (RAR) scheme. This allowed for adjusting the randomization probabilities based on outcomes, favoring more promising arms and potentially dropping poorly performing ones. The probability of randomizing to IA was kept at 1/3 as long as all three arms were active.

After 24 patients were randomized, TI showed poor results, with a randomization probability dropping to just over 7%, leading to its termination. The trial was stopped after 34 patients when TA’s randomization probability fell to 4%. The final success rates were 10/18 (56%) for IA, 3/11 (27%) for TA, and 0/5 (0%) for TI. Due to the RAR design, more than half of the patients (18/34) received the standard IA treatment, which proved to be the most effective. The trial concluded with fewer patients (34) than the planned maximum of 75, though it was noted that recruitment might have been stopped even earlier based on the observed outcomes. If this was traditional randomised clinical trial, we’d have more patients in the inferior arm than what we had in this one!

Overview of this trial using a response-adaptive randomisation design. The probabilities shown are those at the time the patient on the \(x\)-axis was randomised. Coloured numbers indicate the arms to which the patients were randomised

Overview of this trial using a response-adaptive randomisation design. The probabilities shown are those at the time the patient on the \(x\)-axis was randomised. Coloured numbers indicate the arms to which the patients were randomised

5. Concluding thoughts

Securing funding for adaptive designs (ADs) can be challenging due to their complexity and the unfamiliarity of some decision-makers with these methods. It is crucial to present the design in non-technical terms and highlight its advantages over traditional designs. Including an independent assessment report or involving a statistician experienced in ADs can help persuade funders. Adaptive trials require robust monitoring systems to conduct interim analyses accurately and make informed decisions about adaptations. This involves establishing clear rules for interim analysis and ensuring data integrity and timely availability.

In conclusion, adaptive clinical trials offer a promising path forward for medical research. They can accelerate the discovery of effective treatments, optimize resource use, and, most importantly, enhance patient outcomes. As the healthcare landscape continues to evolve, embracing adaptive trial designs will be crucial in meeting the growing demand for innovative and efficient clinical research. By doing so, we can ensure that new therapies are brought to market more swiftly and safely, ultimately benefiting patients and advancing medical science.

In conjunction to adaptive trials, there is also a new type of trials coming in light known as Platform trials. But more on that later someday!

6. References

- Donald Berry et al. ,Adventures in Statistics I: From multi-armed bandit strategies to designs for phase 3 adaptive Bayesian platform clinical trials

- Adaptive clinical trials: a partial remedy for the therapeutic misconception?

- Adaptive designs in clinical trials: why use them, and how to run and report them

- Berry consultants

- Charles Green: Bayesian Adaptive Trial Designs\

- What Clinicians Should Know About Adaptive Clinical Trials